Week #46 - Ezekiel 1-18

Week # 46 Study Page

Ezekiel 1-18

Suggested Daily Reading Breakdown

Sunday: Ezekiel 1-3

Monday: Ezekiel 4-5

Tuesday: Ezekiel 6-8

Wednesday: Ezekiel 9-11

Thursday: Ezekiel 12-14

Friday: Ezekiel 15-16

Saturday: Ezekiel 17-18

Degree of Difficulty: 3 out of 10. Congratulations for making it through Proverbs! This week we’re beginning the last of the 3 major prophets (Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel). Ezekiel is the fifth-longest book in the Bible by word count, because its chapters, on average, are a little longer than normal; that is why our typical reading pace of 23-24 chapters per week is being slowed to just 18. Because Ezekiel is the last major prophet, we are intersecting Israel’s story at its lowest point. Israel has already been carried off by the Assyrians, and Judah’s rejection of God and embrace of idolatry is in full-swing. Ezekiel is the harbinger of the very end for Judah. While reading Jeremiah we noted that there were only brief and sparse passages where Judah was offered an opportunity to repent and be saved from the coming destruction. In Ezekiel, there are no such opportunities for God’s people. This does not mean the Ezekiel is a book without hope. As you read this week you’ll find good news for God’s people, but those blessings are reserved for a time after God’s faithful punishment for Judah’s rebellion. To read any Biblical prophet well, it is crucial to know the historical setting in which he prophesied; we’ll do our best to iron that out below.

Quick Note: Ezekiel is writing long after the fall of the northern kingdom of “Israel” and they (that particular kingdom) are mostly left out his literature. Ezekiel will frequently be using “Israel” and “Israelites” to refer to all of God’s chosen people, instead of using it to refer exclusively to the northern kingdom as elsewhere in the Old Testament.

About the Book(s)

Ezekiel

Date of Authorship: Ezekiel is pretty good about giving historical markers that we can trace back throughout his book. We can use the historical information in 1:2 to date the call of Ezekiel to 593 BC. The last historical marker that we have is in the introduction to Ezekiel’s vision of the restored Jerusalem (40:1) which can be pinpointed to April 28th, 573 BC.

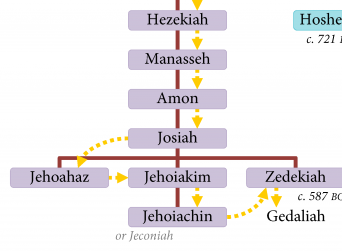

Author: We have every reason to believe that Ezekiel is the author, or at least the speaker, of this book of his prophecy; it is filled with a consistent, first person voice. Ezekiel was a priest who was exiled in the second small (~10,000) batch of prisoners taken by the Babylonians in 597 BC. The first batch in 605 BC is when Daniel, and his friends were taken to Babylon. Ezekiel was exiled together with the Israelite king Jehoiachin, the grandson of Josiah. Ezekiel’s career happens away from the promised land. He is prophesying from Babylon where he is a prisoner.

Her’s a refresher on the final kings of Judah. Ezekiel was deported to Babylon with Jehoiachin

Historical Setting: Ezekiel’s begins when the writing is on the wall for Judah’s demise. Twice already, the resistance of the nation of Judah to control by the Babylonian empire has resulted in military threats, and deportations. The first exiles were taken away in 605 BC, just four years after the death of Josiah, and included Daniel, Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego. The second deportation occurred as a result of further Judahite resistance to Babylonian control and saw the exile of king Jehoiachin to Babylon. In Jehoiachin’s place, Nebuchadnezzar installed his uncle Zedekiah who had sworn loyalty to the Babylonians. It is a this moment that Ezekiel begins to prophecy. during Ezekiel’s career, Zedekiah will ally with Egypt against Nebuchadnezzar, and that rebellion will result in the total devastation of Jerusalem at the hand of the Babylonians, and a large exile of people out of the promised land.

Purpose: Ezekiel is commissioned to bring charges against Judah for violating their covenant with God before the arrival of God’s Judgment. In service to that role, Ezekiel is explaining God’s anger and justice while remarking upon the utter unfaithfulness of His people. But that is just one pole of Ezekiel’s message. Ezekiel is also a deliver of hope. God uses Ezekiel to tell his people that there will be restoration on the other side of Judgment, because God’s faithfulness will not fail them. C. Hassell Bullock puts it best:

Ezekiel, as clearly as any of the prophets, set up the opposite poles and then showed how Yahweh resolved the polarization. On the one hand God declares that He will turn His face from Israel, and on the other that he will not hide His face from them anymore. At one pole Israel drives Yahweh from His sanctuary, and at the other Yahweh gives instructions for a new Temple where he will take up His everlasting residence. The glory of the Lord leaves the Temple, and it returns. He gives up the land to destruction so that even Noah, Daniel, and Job could not save it, and He reclaims and repartitions the land for His people. On the one side Israel breaks the Mosaic covenant, and on the other the Lord establishes and everlasting covenant. The shepherds neglect His flock, and He Himself becomes the Good Shepherd. Israel’s idolatrous abominations are pitted against Yahweh’s holiness. Repentance has a low profile in the book, giving place to Yahweh’s initiative to bring about the drastic changes that could save and restore Israel. (An Introduction to the Old Testament: Prophetic Books, 305)

As You Read Notes:

Ezekiel 1:1 The Thirtieth year

We’re given two descriptions of the same date in Ezekiel 1:1-2. The most helpful description is the “fifth year of the exile of King Jehoiachin” which allows us to assign a year to the beginning of Ezekiel’s ministry (593), but assigning meaning to the first date has proven to be very difficult. There have been three main theories advanced concerning what the “thirtieth year” means in verse 1

The first theory is that there are actually two different dates being described in verses 1-2 . The date in verse 1, would be the thirtieth year of the exile of king Jehoiachin - which would be 25 years after the visions beginning in 1:2. Those who hold this theory see verse 1 as an introduction to when the book is being published by Ezekiel, and verse 2 as describing the beginning of Ezekiel’s ministry (Proponents include E.G. Howie, and William Albright).

the Jewish Targum claims that the “thirtieth year” is counted from Josiah’s reform which was declared a year of Jubilee. The year of Jubilee was supposed to be celebrated every fifty years, so it would be natural to record a date according to this benchmark. In this and the following theory, the dates in verses 1 and 2 are coincidental.

Finally (the theory which I prefer) the thirtieth year could be a reference to Ezekiel’s age. This is roughly how old we expect Ezekiel to be in 593 and the thirtieth year is when a priest would fully enter into his profession (see Numbers 4:3, 30, 35,43,47). Thus Ezekiel would be telling us that his vision occurred at the beginning of his priestly ministry . (proponents include Moshe Greenberg and R.K. Harrison)

Ezekiel 1: Ezekiel’s vision

I don’t believe that there is any artist’s rendering that could capture what Ezekiel is depicting for us in chapter 1 when he describes the theopany which he witnesses. There are really no ancient Near Eastern parallels to what Ezekiel describes, especially as it relates to the multi-faced creatures described here. Along with the wheels which could move in any direction, the purpose of the multiple faces of the beasts show the power of God to be present everywhere and to be aware of all events on earth. In ANE iconography, the lion indicates strength (2nd Samuel 1:23), the eagle indicates speed and gracefulness (Isaiah 40:31), and the ox indicates fertility (Psalm 106:19-20).

Ezekiel 4:12, 15: Fuel for the Fire

Ezekiel was given more than just words by which to communicate to the Israelites. More than any other prophet (with Hosea as a close second), Ezekiel was asked to lived out his message to God’s people:

Ezekiel’s symbolic actions were numerous, surpassing even Jeremiah… In these actions, message and messenger were combined into one inseparable mode of communication. Consistently some words of interpretation accompanied them, and most often the dramatic signs focused on the destruction of Jerusalem and the resulting conditions of siege and exile. Walther Zimmerli and others have drawn attention to the interesting idea that Ezekiel took several metaphors found in other prophets and enacted them literally; for example, Jeremiah’s metaphor of eating the Lord’s words (Jeremiah 15:16) and Ezekiel’s actual consumption of the scroll(3:1-3), Isaiah’s metaphor of shaving Israel with a razor (Isaiah 7:20) and our prophet’s literal shaving of his head and beard (5:1-4). (C. Hassell Bullock, An Introduction to the Old Testament: Prophetic Books, 282-283)

Consider that Ezekiel had to lay on his side for four-hundred-&-thirty days! Furthermore, Ezekiel’s calling takes a turn for the gross when he is told by God to cook his food over human waste (4:12). This was to signify that the Israelites would eat defiled foods (i.e. food that were unclean, and meat that had been sacrificed to pagan Gods) in the land where the were, and would be exiled. However, God yields to Ezekiel’s complaint about this requirement, and God allows him to use animal waste. To the modern reader this certainly seems preferable, but maybe not much* better. However, cow dung was an extremely common fuel for fire in the ancient world, especially in Palestine, where timber was sparse.

The typical fuel in areas like Mesopotamia and Palestine was dried animal dung or cakes made from the waste pulp of crushed olives. Trees were too precious to be cut for cooking and warming. (IVPBBC:OT, 693)

Ezekiel 9:4 the mark of the pure

You’ve probably heard of the “Mark of the Beast” which comes from this passage in Revelation

It also forced all people, great and small, rich and poor, free and slave, to receive a mark on their right hands or on their foreheads, (Revelation 13:16)

But had you heard of the mark of the pure? Look What God tells his messenger (the “man clothed in linen”) to do here in Ezekiel 9:4

“Go throughout the city of Jerusalem and put a mark on the foreheads of those who grieve and lament over all the detestable things that are done in it.”

This mark was for those in Jerusalem who did not practice the idolatry and paganism which Judah had descended into. The word translated “mark” in your Bible is literally the Hebrew letter “taw”. While this passage seems to reflect a spiritual reality and not a physical one, the mark in question was almost certainly the Hebrew letter indicated in the text.

In the script used during Old Testament times it was either in X shape or a + shape. It may represent God’s ownership of the remnant of the people who deserved to survive the coming destruction. Jewish tradition continued to employ this sign as a mark of the righteous as we know from the Dead Sea Scrolls, though the intertestamental period and into rabbinin traditions. This marks’s resemblance to a cross made the symbol unpopular among the rabbis in the post-Christian era. (IVBBBC: OT, 697)

Isn’t it cool to think of the pure in Jerusalem being marked with the cross shape by God to be rescued from his punishment? Early in the history of the Church, there developed a tradition of making the sign of the cross on one’s forehead. The earliest witness to this practice in the Early Church Fathers is that of Turtullian, writing De Corona in approx 201 AD

“In all our travels and movements, in all our coming in and going out, in putting on our shoes, at the bath, at the table, in lighting our candles, in lying down, in sitting down, whatever employment occupies us, we mark our foreheads with the sign of the cross”

The origins of this tradition were not explicitly tied to this passage in Ezekiel 9. But by the time the 5th century arrived. Jerome, a great teacher of the Church, and one of the most accomplished masters/students of the Scriptures, had thoroughly connected the tradition with this passage (Ezekiel 9:4), and this is the origin of the tradition of the “sign of the cross” which you witness in Catholic and Orthodox churches today. Its not something that we, as Protestants, need to be scared of or avoid, feel free to think of Christ’s saving work and Ezekiel 9 if you wish to join your Catholic brother or sister in making the sign.

Ezekiel 10:1 The Glory Departs

I was unfamiliar with the term “Lapis Lazuli” which appears often in Ezekiel when he see’s a vision of God, as here in 10:1. it is a gem stone, and is pictured here

Ezekiel, though he was living in Babylon, was taken by God to witness certain conditions and visions of the promised land and Jerusalem. Notice the way that Ezekiel describes his mode of transportation for these visions:

I looked and saw a figure like that of a man…He stretched out what looked like a hand and took me by the hair of my head. The Spirit lifted me up between earth and heaven and in visions of God he took me to Jerusalem” (Ezekiel 8:2-3)

That does not sound like a very comfortable ride! Ezekiel see’s something terrible happen in chapter 10. Ezekiel witnesses the Glory of God depart from the Temple. God’s glory lifts from above the mercy seat, leaves the temple through the east gate and continues east up the Mount of Olives (12:23).

Ezekiel 14:14: Noah, Daniel, and Job

Here in Ezekiel 14, God is making the point that Jerusalem will not be saved just because it has a few righteous people in it. He uses three characters of faithfulness to make His point, that the righteousness of a few will not shield an entire wicked people, clarifying that even these heroes would only be able to save themselves from the coming judgment. Noah is the perfect case study for this teaching because only he and his family were saved from the destruction of the flood. Job is a man who generally remained faithful through suffering and was considered righteous by God himself. Daniel is a really strange inclusion to this list. Daniel is a contemporary of Ezekiel! He would have still been alive when Ezekiel wrote these words. Daniel was deported to Babylon in 605 BC, just 8 years before Ezekiel was, they likely knew each other!

It has seemed unlikely to many interpreters that Ezekiel would place a contemporary prophet, Daniel, in this group. This chapter however, likely dates from the late 590s. By that time Daniel had been in Babylon for almost fifteen years and would have been in his late twenties or early thirties. His (Daniel’s) success had come early, so he had been in a high position in the court for a decade. Nevertheless, Daniel does not mesh easily with the profile of the other two. First, both of them (Noah and Job) are non-Israelites….some interpreters have considered it possible that the Daniel mentioned here refers to “Danil,” the wise king of ancient Ugarit who was the father of the hero Aqhat.